2. What Is A Type Of Veterinarian That Only Practices On Small Companion Animals?

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Demographics of dogs, cats, and rabbits attending veterinarian practices in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland every bit recorded in their electronic health records

BMC Veterinary Research volume 13, Commodity number:218 (2017) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Understanding the distribution and determinants of disease in animal populations must be underpinned by knowledge of brute demographics. For companion animals, these data take been hard to collect because of the distributed nature of the companion animal veterinary industry. Hither we describe key demographic features of a large veterinary-visiting pet population in Great Britain as recorded in electronic health records, and explore the clan between a range of animal'southward characteristics and socioeconomic factors.

Results

Electronic health records were captured past the Small Brute Veterinary Surveillance Network (SAVSNET), from 143 practices (329 sites) in Britain. Mixed logistic regression models were used to assess the association between socioeconomic factors and species and breed ownership, and preventative health care interventions. Dogs fabricated up 64.8% of the veterinary-visiting population, with cats, rabbits and other species making upwardly 30.3, 2.0 and 1.6% respectively. Compared to cats, dogs and rabbits were more likely to exist purebred and younger. Neutering was more common in cats (77.0%) compared to dogs (57.1%) and rabbits (45.eight%). The insurance and microchipping relative frequency was highest in dogs (27.9 and 53.ane%, respectively). Dogs in the veterinarian-visiting population belonging to owners living in least-deprived areas of Nifty Britain were more probable to be purebred, neutered, insured and microchipped. The same association was found for cats in England and for certain parameters in Wales and Scotland.

Conclusions

The differences we observed within these populations are likely to bear upon on the clinical diseases observed within private veterinary practices that treat them. Based on this descriptive study, there is an indication that the population structures of companion animals co-vary with human and ecology factors such as the predicted socioeconomic level linked to the owner's address. This 'co-demographic' data suggests that farther studies of the relationship between homo demographics and pet ownership are warranted.

Groundwork

Individuals inside a pet population vary according to a wide range of characteristics including age, sexual practice, species and breed. Since the species and breed of each individual animal are largely under the control of the owners, this variation is likely to be heavily impacted by man behaviour. Agreement demographic variation is critical to reducing illness risk and predicting the possible furnishings of interventions, and increasingly to the design of personalised health plans [ane].

Demographic data may be available in some countries where it is required past regulators. Yet, in the absenteeism of legislation, information are oft lacking, and where present, driven by market forces. This is the instance for companion animals in many countries, where there is no compulsory registration and lilliputian statutory disease notification. The companion animal sector is highly contained of government and whilst there is undoubtedly a wealth of demographic data generated, it is ofttimes fragmented in local databases and therefore non readily available for analysis [1]. Primary information collections can be fabricated, just they are costly and time-consuming to constitute and maintain.

Data on population demographics in the small animal sector has generally been obtained using cantankerous-sectional surveys linked to specific studies [one,2,3,four,v]. Cohort studies could provide deeper epidemiological insights, as they oft practice in human wellness [6, 7]. Still, data from companion animal cohorts are just at present starting to become bachelor [8, 9].

As a result, others have sought to harness existing databases such equally pet health insurance data, microchipping, and pedigree registers which may be more than accessible and cost effective, but every bit they only correspond sure subpopulations they are prone to bias. Insurance databases tin be useful for longitudinal studies [10, 11], merely their data are generally only on diseases that result in claims [12]. Similarly, microchipping and pedigree registers do not represent the general population, although this situation is irresolute for dogs as microchipping has recently get compulsory in the Great britain [13].

Evidence suggests that in countries with developed pet industries, a loftier proportion of owned pet animals attend a veterinary surgeon [1, fourteen]. Asher et al. [1] estimated that 77% of the owned dogs in the UK were registered with veterinarian practices and argued that surveys of veterinary practices could be useful in estimating the demographics of the owned canis familiaris population.

Every bit health records become digitised they become more available for enquiry [15]. In 1999, Lund et al. [14] used such records to explore population demographics in the Usa. However, the records were manually supplemented with additional questionnaire data by practitioners and often data were available for only a minor proportion of the sampled population. In England, O'Neill et al. [sixteen] successfully collected electronic health records (EHRs) from a large population of animals; however, most of the practices were from simply 2 regions restricting national generalisability.

SAVSNET, the Small Animal Veterinary Surveillance Network collects anonymised EHRs in real time from veterinary surgeons in practice and from commercial diagnostic laboratories throughout the UK, making them available for research [17, 18]. Data supply has been maintained by limiting the additional workload of participating practices and providing near-real-fourth dimension benchmarking to data providers.

The objective of this written report was to apply EHRs collected over a full yr by SAVSNET to depict the demographics of a diverse veterinary-visiting population of small-scale companion animals across England, Scotland and Wales. In addition, we explored associations between a range of creature characteristics, including preventive health care interventions (such equally neutering and insurance), and the socioeconomic condition relative to the location of its owner. The methodology described ways the results presented could be efficiently updated to monitor future trends over fourth dimension.

Methods

Information collection

Information were collected electronically in well-nigh real-time from volunteer veterinarian practices using a compatible version of do direction organization (PMS) namely RoboVet (Vetsolutions, Edinburgh) and Teleos (Birmingham). Practices using these PMSs were approached and those expressing a willingness to participate in SAVSNET during a phone call were recruited. A 'exercise' is defined equally a unmarried veterinary business organisation, whereas 'premise(s)' includes all branches that make up a practice. This cantankerous-sectional written report uses a year of data from 143 of these practices (329 bounds), chosen because they submitted uninterrupted data between 1st Nov 2014 and 31st October 2015, and represented 91.7% of total practices recruited by SAVSNET at the end of the written report catamenia and effectually 5.6% of UK veterinary practices (denominator from [1]). One hundred and 20-four practices (295 premises) were recruited from England, 8 practices (17 premises) from Scotland and 11 practices (17 premises) from Wales (Fig. 1). The EHRs were nerveless from consultations where a booked engagement was made to run into a veterinary surgeon or nurse, and include the date the animal was seen, anonymous identifiers for each practise, premise and animate being, the animal signalment (including species, breed, sex activity, neutering status, date of birth, date of neutering, insurance and microchipping condition) and full possessor'south postcode.

Geographical distribution of veterinary premises (Due north = 329; black circles) and animals (grey crosses) of the study. The boundaries for Nifty Uk describe the regions considered in the study (i.e. the countries of Scotland and Wales and the English language regions of East Midlands, East of England, London, North East, North West, South East, South West, West Midlands, Yorkshire and The Humber). The reference map layers used contain: National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2011 and 2012, NRS information © Crown copyright and database right 2011 and Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database correct 2011 and 2012

Owners attending practices participating in SAVSNET are informed about the project by a waiting room affiche; those wishing to opt out are invited to tell their practitioner, who can then exclude all their data from the written report. These opted out consultations are quantifiable for each practice, but no further data are captured past SAVSNET.

The drove and utilize of these information was approved by the Academy of Liverpool'south Inquiry Ideals commission.

Data direction

The text-based data were cleaned for species and brood to deal with misspellings or the use of non-standard terms by mapping to standard terms. This was a two stage procedure of discovering the not-standard terms then developing/applying mapping rules. For example, to map the breed names (especially dogs, cats and rabbits) a standard list of the most mutual breed names was taken from a reliable source (due east.1000. the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland Kennel Club for dog breeds). Each non-standard brood name in the clinical tape was mapped to the standard name manually on its kickoff occurrence. Further occurrences would then be matched automatically. Many breeds were present in the data set, some represented by only a few individuals, limiting further brood analysis. Thus, for the purposes of this study, only the creature'due south breed, classified as purebred or crossbred, was further assessed.

Information from multiple visits for individual animals was included in the concluding analyses equally follows. For animals attention veterinarian practices on more than one occasion their age was calculated as the median age of all animate being-age observations. These animals were considered to be neutered and/or insured and/or microchipped if these parameters were positively recorded on at least one consultation. Age at which an brute was neutered was calculated using the appointment of birth and the date of neutering when both parameters were captured. Afterwards examining and removing the outliers from the age profile of each species, the upper age limit for dogs, cats and rabbits was established as 24.5, 26 and fifteen.five years one-time respectively.

Postcodes of owners were used to link each animal to the National Statistics Postcode Directory [19] and information concerning geographic location, i.eastward. state, region, Lower layer Super Output Area (for England and Wales) and datazone (for Scotland) classification. Regions in U.k. were defined using level 1 of the Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics (Nuts) which includes the countries of Scotland and Wales and the English regions of East Midlands, East of England, London, North Eastward, Due north West, S East, Due south West, West Midlands, Yorkshire and The Humber (Fig. i). The postcodes were besides used to match each animal against databases containing Alphabetize of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) ranks for England 2010 [20], Scotland 2012 [21] and Wales 2011 [22]. A detailed description of how each government has adult their own measure of deprivation tin can be found elsewhere [23,24,25]. As a event IMD measures between these countries are non straight comparable. In England and Wales, the ranks of the Index are calculated for each Lower layer Super Output Area, whilst in Scotland these are calculated per each datazone. Ranks of the IMD for England, Wales and Scotland were independently categorised based on quintile cut-off scores with category ane being least deprived and category v, the almost deprived.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise key demographic variables of this particular veterinarian-visiting pet population and therefore statistical analyses were only required where specific associations between the exposure(south) and issue(south) of involvement were evaluated.

The asymptotic, linear-past-linear association exam allows testing of the independence of 2 factors in case either both or one factor are ordered factors (i.east. ordinal variable) stratified by a third factor. A general clarification of this method is given past Agresti [26]. This method implemented in the R package 'coin' was performed to examination whether in that location was a significant association between species (i.e. dogs and cats) and the age at which animals are presenting to SAVSNET veterinary practices. The continuous age variable was categorised every bit young (<one year old), adult (1 to <8 years old) or aged (≥8 years onetime) as previously [17]. Age was considered in the test as an ordinal variable and the analysis was stratified by practise. The same analysis was conducted to assess whether there was an association between breed and age in dogs and cats. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Mixed furnishings binary logistic regression models, incorporating veterinary practices as random effects, were used to assess the strength of association between the fixed upshot IMD and several outcome variables such as dog buying, true cat ownership, breed buying, ii sex-neutering binary variables (with ane being the neutering status in males and the other the neutering status in females), insurance status and microchipping status of dogs and cats. The association between IMD and each of these 2 sex-neutering binary variables was assessed using individual models. Separate models were undertaken for animals living in England, Scotland and Wales. Regression models were not conducted for rabbits because they are underrepresented in many veterinarian practices as well as in categories of the explanatory variable and outcome variables, specifically in Wales and Scotland. The models were fitted using the Gauss-Hermite quadrature method with ten quadrature points per scalar integral implemented in the R package 'lme4'. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Statistical analyses were carried out using R language (version 3.0.one) [27].

Results

Full general demographic statistics

Number of animals and age profile of dogs, cats and rabbits

Information from 526,431 individual consultations were recorded, which represented 77.7% of total consultations including those where the client had opted out of study participation. When repeated consultations were removed, this included 186,044 unique dogs (64.8%), 86,995 cats (30.3%), 5626 rabbits (2.0%), 4684 other species (1.6%), and 3891 unmapped species (1.3%), the latter including 41% of animals where the species was originally unknown or not recorded. The geographical distribution of all animals included in the electric current report is presented in Fig. 1. The mean number of consultations per creature during the study period was 2.0, 1.half dozen, 1.six and 1.4 for dogs, cats, rabbits and other species respectively.

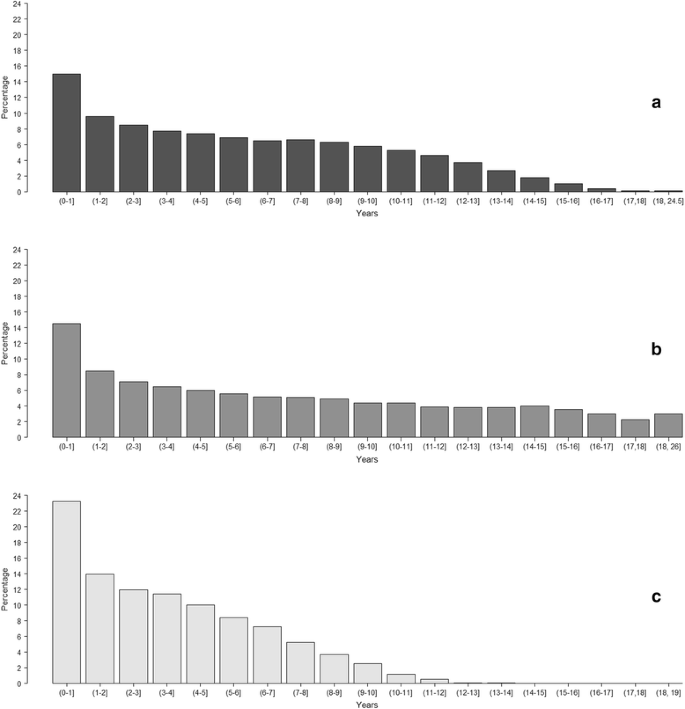

The historic period profile of dogs, cats and rabbits presenting to SAVSNET veterinary practices is shown in Fig. 2. The percentage of dogs, cats and rabbits in which the date of nativity was not recorded was ane.three% and the percentage in which it was considered not authentic was less than 0.01%. The median age, based on the median historic period of all an animal's individual age observations, was v.2 years in dogs (minimum value - maximum value: 0–24.five years; interquartile range: 7.0 years), 6.2 in cats (0–26.0; 9.4) and three.0 in rabbits (0–15.5; 4.4). The proportion of dogs and cats attending to SAVSNET veterinary practices during the study period was not the same for the 3 age categories (χ two df=1 = 1237.7; P < 0.001), with a greater proportion of cats presenting when over eight years of age than dogs (Table ane).

Historic period profile of dogs (a), cats (b) and rabbits (c) presenting to SAVSNET veterinary practices

The Table shows the number and percentage of total number of animals past species (i.due east. dogs and cats), brood and by age category. For both species, the number of purebred and crossbred animals does not sum up to the full number of animals because a mapped breed was not available for all individuals.

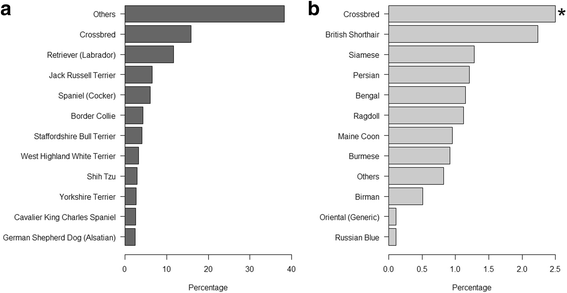

Number of animals by breed in dogs, cats and rabbits, and historic period profile by brood in dogs and cats

A mapped breed was available for 87.7% of all dogs, cats and rabbits. The remainder included animals where the breed recorded comprised a large number of rare misspellings as well as animals where the breed was either unrecorded or not recognised by the practitioner. Where a mapped breed was available, 84.1% of dogs and 98.2% of rabbits were recorded as purebred. This was in stark contrast to cats where the figure was much lower (10.4%). The 10 well-nigh popular purebreds accounted for 74,648 dogs (45.9%) and 7634 cats (9.6%) (Fig. 3). Labrador Retriever (11.6%) and British Shorthair (2.2%) were the nearly popular breeds of dog and cat, respectively.

Percentage of total dogs by dog breed (a) and total cats by cat breed (b). The asterisk (*) indicates that the percent of total cats represented by crossbred cats was limited for presentation purposes because they represented such a large proportion of the population; crossbred cats accounted for 89.6% of total cats in this population

The proportion of crossbred cats and purebred cats attending to SAVSNET during the report period was non the same for the three age categories (χ ii df=1 = 61.6; P < 0.001), with a greater proportion of crossbred animals presenting over 8 years of age (Table 1). This human relationship between purebred status and age was not significant in dogs (χ 2 df=1 = 0.5; P = 0.five).

Number of animals by sexual activity in dogs, cats and rabbits

In the veterinary-visiting population assessed, there were approximately equal numbers of female and male dogs and cats with females making upwardly 49.three% of dogs and 51.nine% of cats. The same was true in each species at breed level, with females making up 49.1% of purebred dogs, 50.1% of crossbred dogs, 48.2% of purebred cats and 52.1% of crossbred cats. In rabbits, at that place was some deviation from this with females making upwardly 43.7% of all rabbits, 41.eight% of recorded purebred rabbits and 30.0% of recorded crossbred rabbits.

Key functioning indicators (KPIs) statistics

Neutering status

Over one-half of dogs were neutered (57.one%), including 55.0% of males and 59.2% of females. In this veterinarian-visiting population neutering was more common in cats (77.0%), including 78.4% of males and 75.eight% of females. Less than half of the rabbits were neutered (45.eight%), including fifty.0% of males and forty.3% of females.

In this SAVSNET written report population the neutering relative frequency was higher in male person crossbred dogs (62.5%) than in male purebred dogs (53.43%) and in female person crossbred dogs (65.ane%) than in female purebred dogs (58.6%). In cats, the percentage of neutered animals was slightly higher in male purebreds (eighty.1%) than in male crossbreds (79.one%) and in female person crossbreds (77.4%) than in female person purebreds (75.iii%). In rabbits, the neutering relative frequency was higher in male person purebreds (52.7%) than in male person crossbreds (28.6%) and college in female crossbreds (50.0%) than in female purebreds (41.3%).

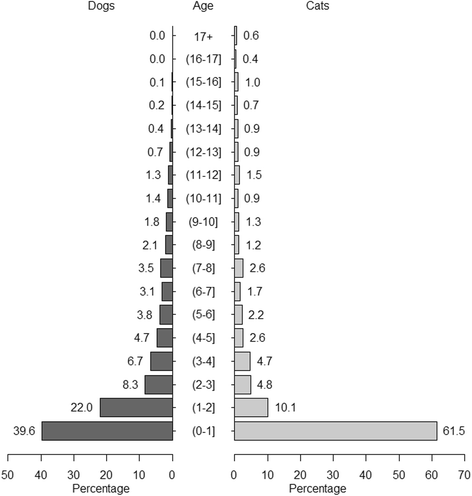

The age of neutering was recorded in 51.2% of neutered dogs and 42.3% of neutered cats. For these animals, the recorded age at neutering is shown in Fig. 4, with 39.vi% of neutered dogs and 61.5% of neutered cats recorded as existence neutered within their showtime year of life. Fig. five shows a higher age resolution of the percentage of neutered dogs and cats in their outset year of life, suggesting that in both species, neutering peaks at around 180 days of age. This equates to only 0.7 and six.9% of all neutered dogs being neutered within the first four and 6 months of life respectively. In cats, these percentages were higher, with 3.iii and thirty.5% of all neutered cats being neutered inside the first iv and 6 months of life respectively.

Age (in years) at time of neutering in dogs and cats. The percentage of dogs and cats neutered at a given age, for the 51.two% of neutered dogs and 42.3% of neutered cats where this historic period was known

Age at fourth dimension of neutering for dogs and cats neutered in their outset yr of life. The percentage of dogs and cats neutered is shown for ten twenty-four hour period intervals

Insurance and microchipping condition

The recorded relative frequency of insurance for dogs, cats and rabbits was 27.9, 18.5 and 9.one%, respectively. The recorded per centum of insured animals was slightly higher in purebred dogs (28.four%) than in crossbred dogs (26.8%) and higher in purebred cats (24.7%) than in crossbred cats (18.2%).

More than than one-half of dogs (53.1%) were recorded as being microchipped, whilst just 39.9% of cats and iv.4% of rabbits were microchipped. Similar insurance, in this SAVSNET study population the microchipping relative frequency was higher in purebred dogs (53.8%) than in crossbred dogs (fifty.7%) and college in purebred cats (44.eight%) than in crossbred cats (xl.0%).

Geographical area and practice

The main demographic outcomes obtained for this SAVSNET veterinary-visiting population are summarised at geographical and practice level in two additional files [see Additional files 1 and two, respectively]. Rabbits were excluded from the results at practice level because they were underrepresented in a big number of practices.

Socioeconomic condition

In 94.six% of all animals where the owner had not opted out of study participation, a valid owners' full postcode was recorded, which immune them to exist matched against national databases linking geographic location with IMD ranks.

Species and breed buying

The distribution of animals by species, British country and IMD category is shown in an boosted file [come across Boosted file iii]. Of the animals presented to these SAVSNET practices, the odds of the animal being a canis familiaris (compared to non-dogs) were significantly lower if its owner was living in lesser deprived areas of England, Wales and Scotland than the most deprived areas of these countries (England: P < 0.001 for IMD categories 4 and 1, P < 0.01 for IMD 3, and P < 0.05 for IMD 2; Wales: P < 0.001 for IMD categories 3 and 2, and P < 0.05 for IMD iv; Scotland: P < 0.01 for IMD 1, and P < 0.05 for IMD 2) [see Additional file iv for detailed statistical output]. The contrary association was true in cats [Boosted file 4].

Of the dogs attention SAVSNET practices, the odds of the animals being purebred were significantly higher if their owners were living in lesser deprived areas of England rather than the most deprived areas of the land (P < 0.001 for IMD categories 1–iii) [Additional file 4]. In Wales and Scotland, this association was only significant in IMD category two (P < 0.01) and IMD category i (P < 0.05) [Boosted file 4], respectively. For cats, the same association was significant in England for IMD categories 1–3 (P < 0.001) and it was non significant in Wales and Scotland [Additional file four].

Neutering, insuring and microchipping status

A pregnant relationship was found between being neutered, insured or microchipped and the predicted IMD based on the location of the pet owner [see Additional file 5 for detailed statistical output]. Of the male person and female dogs attending SAVSNET practices, the odds of being neutered were significantly college if their owners were living in lesser deprived areas of England, Scotland and Wales rather than the nigh deprived areas (male: P < 0.05 for IMD categories 1–4 in England and Wales, and IMD 1–3 in Scotland; female: P < 0.05 for IMD 1–4 in England, Wales and Scotland). The same association was plant for male and female cats in England (P < 0.05) and male person cats in Wales in IMD categories one–iii (P < 0.05) and for male and female cats in IMD category 1 in Scotland (P < 0.05) [Boosted file 5].

For dogs, the odds of beingness insured and microchipped were significantly college if their owners were living in lesser deprived areas of Great Britain rather than the near deprived areas (insurance: P < 0.05 for IMD categories ane–4 in England and for IMD 1–3 in Wales and Scotland; microchipping: P < 0.05 for IMD categories 1–4 in England and Scotland, and IMD ane–3 in Wales) [Boosted file 5]. The same association was found for cats in England and Wales (P < 0.05) [Additional file five], except for cats being microchipped in the IMD category 2 in Wales. In Scotland, this association was only meaning for cats being microchipped in IMD category 1 (P < 0.05) [Additional file 5].

Discussion

Demographic variables influence wellness and welfare in humans and animals through at least two interrelated phenomena, namely the population'southward characteristics (its size and its limerick past age, sex, species, brood, etc.) [28] and the characteristics of the surround in which a given population alive (e.g. geographical distribution, socioeconomic factors). Application of disease control measures and possible interventions require an understanding of the demographic context and how it is changing over fourth dimension. This written report has used routinely collected EHRs from volunteer veterinary practices to describe primal demographic variables of a large population of veterinary-visiting companion animals across Britain.

Species presenting to practise

The proportion that dogs, cats, rabbits and other species represented in our population was consistent with comparable studies [18, 29]. At that place is now a confluence of information from disparate sources to suggest the numbers of owned cats and dogs are broadly similar in the Britain. Based on a telephone survey in 2011, there were an estimated 11,599,824 dogs (95% CI: x,708,070–12,491,578) and 10,114,764 cats (9,138,603–11,090,924) in the U.k. [xxx]. Although non peer reviewed, the Pet Food Manufacturers' Association publishes more often than not accustomed estimates of pet ownership with most recent figures for 2015 estimating 8.five one thousand thousand dogs, 7.four meg cats and 1.0 1000000 rabbits in 24.0, 17.0 and ii.0% U.k. households, respectively. It is therefore interesting that individual dogs both made upwardly a ii.1-fold greater proportion of the veterinary-visiting population of this study than cats, and also that, on boilerplate, each private dog attended a SAVSNET veterinary surgery 1.2 times more than oftentimes than cats. This raises important clinical and social questions on how often individual cats and dogs get sick, how oft they are recognised equally being sick by their owners, and how motivated their owners are to seek veterinarian care either when ill, or for other preventive wellness intendance when well.

Association between postcode predictors of deprivation and species ownership

Considering SAVSNET collects full owners' postcodes, each EHR can be matched against published predictors of homo socioeconomic deprivation. Here we testify that regardless of predicted deprivation, dogs ever made up the largest proportion of species presented to their veterinarian. However, the odds of the animal being a dog (compared to non-dogs) were significantly lower if its owner was living in lesser deprived areas of Great Uk than the most deprived areas of the country. The reasons for this are not clear, but it may be that owners in the most deprived areas take their dog to the veterinarian more frequently than they practice in lesser deprived areas. Alternatively, dogs may comprise a larger proportion of species living in the most deprived areas than in bottom deprived, or owners may take other species to the veterinary less often than they do in lesser deprived areas, or at that place may be a combination of such factors. Since nearly of non-dogs were cats, not surprisingly the reverse association was truthful in cats. Other studies have shown a similar clan of socioeconomic factors and cat ownership in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and elsewhere. In a phone survey, although household income itself was not pregnant, households containing ane or more people with a university caste were 1.36 times more likely to own a cat than other households [three]. In the U.s.a., true cat ownership, as measured by the presence of cat allergens, was more mutual in households where the mother had a college level of schoolhouse education [31] and in areas with low levels of poverty [32]. The reasons for this correlation betwixt socioeconomics and pet preference are probable to exist complex. Nevertheless, since they will impact on brute welfare and human health, they warrant further enquiry.

Breed status

Whilst the vast majority of dogs (84.1%) and rabbits (98.ii%) in the veterinary-visiting population of this study were considered purebred, the opposite was the case for cats (10.iv%). This is broadly consequent with previous studies in dogs in the United kingdom [sixteen, 29], and elsewhere [11, 14], and cats [14, 29, 33]. These findings reaffirm the want of the public in Great Britain to ain dogs of a recognisable breed, and may explain in role the highly developed and diverse canis familiaris breeding industry in the UK and elsewhere. Consistent with previous studies, the Labrador Retriever was the most mutual breed in this population [1, 16, 34]. Indeed the meridian half dozen breeds reported hither were the same as those described based on an entirely dissimilar do data set (Sánchez-Vizcaíno F: Population demographics, unpublished).

Historic period contour of species and breeds

Cats' median age (6.two years) was higher than dogs (5.2) and rabbits (three.0), demonstrated by a greater proportion of cats over the historic period of viii in the studied population. This was consistent with previous figures based on a smaller population of observed consultations [4]. Interestingly, a significant association was likewise found between breed and the age category at which cats attended SAVSNET veterinary practices, with a greater proportion of cats over the age of 8 years presenting in the crossbred group. The ages used are those at presentation to a veterinary surgeon or nurse and may be affected by many factors including an individual animate being's underlying susceptibility to disease, and socioeconomic factors of their owners. Therefore, further studies aimed to sympathise the patterns of morbidity with age as well equally life expectancies in breeds of dogs and cats are required.

The dogs and cats in our report were somewhat older than those in previous like studies based on EHRs by O'Neill et al. [16] (dogs 4.v years) and Lund et al. [fourteen] (dogs 4.8 years and cats four.3 years). Whilst the reasons for this are unknown they may relate to differences between the sampled populations and how individual EHRs are collected; historic period in the current study was based on booked consultations whereas other studies may only require that animals are under veterinarian intendance.

Pet neutering condition and age of neutering for each species

That neutering is an effective intervention to preclude unwanted pregnancy in companion animal species is without dubiety. Nonetheless, neutering in companion animals is used for many other reasons such every bit affliction prevention and behaviour modification [35]. In our population, neutering was more mutual in cats (77.0%), than in dogs (57.1%) and rabbits (45.8%). These values for dogs and cats are broadly similar to those in other studies in the UK including cats ([ix] – 73.5%) and dogs ([36] – 49.8%, [16] – 41.ane%, [37] – 54.0%). Where both cats and dogs have been included in the same report the trend to neuter cats more than dogs is likewise conserved: in the UK [38], in Ireland [2], and in the USA [xiv]. Within species, there were also interesting differences in our population between the neutering of the sexes. For cats, males were more than oftentimes neutered than females, perchance reflecting owner concerns around the behaviour of unabridged tomcats, and also the relative ease and lower cost of neutering in males. This tendency was reversed in dogs, consistent with a survey showing veterinary surgeons were more likely to recommend neutering of female person dogs than male dogs [37]. This pattern has also been observed in other studies [2, iv, fourteen], suggesting that adequately consistent underlying pressures are driving the neutering of pet animals in disparate populations (UK, Ireland, The states). Differences observed between the neutering frequencies of purebred and crossbred animals in all species are likely to outcome from complex interactions betwixt owner demographics and intentions to brood.

Guidelines encourage neutering of cats soon after the showtime vaccinations are complete and at around 4 months-of-age [39, 40]. Neutering cats prior to sexual maturity is strongly recommended to prevent unintended litters, and to avoid neutering of female cats while they are pregnant [41]. Furthermore, cats neutered by four months of age were shown to have significantly lower complication rates [42] with shorter surgery duration, lower surgical morbidity rates and quicker recovery from anaesthesia compared with cats neutered at half-dozen months of age or older [43,44,45]. In our study population, based on the recorded neutering date and historic period, only approximately ane 3rd of neutered cats were recorded every bit being neutered within their first vi months of life. This points to a meaning proportion of cats where current guidelines may not be beingness followed, with potential impact on beast welfare, both directly, and through an increased adventure of unwanted pregnancies.

Guidelines recommending the age of neutering are less definitive for dogs; according to the British Veterinarian Association [35], there is bereft data to form a position on the early neutering of dogs. Our study, showed that only 6.9% of neutered dogs were recorded equally being neutered within their outset 6 months of life.

Owner predicted deprivation was too associated with the neutering frequency. Both for male person and female dogs attending SAVSNET practices, the odds of being neutered were significantly college if their owners were living in lesser deprived areas of Bang-up U.k. than the most deprived areas of the land. The same association was plant for male and female person cats in England and male cats in Wales and a similar although less clear trend was seen for male person and female cats in Scotland. Our previous airplane pilot report based on data nerveless in a similar way but from a dissimilar PMS and dissimilar smaller populations distributed through England and Wales plant similar results [46]. Within cats, factors including increased household income and obtaining their true cat from a rescue organisation were positively associated with increased neutering past 6 months-of-age [9]. In futurity studies it will be critical to consider the wellness psychology underlying possessor choices to neuter their pets.

Pet insurance condition for each species

The relative frequency of insurance in pets is more often than not considered to be relatively loftier in the Uk compared to another developed countries such equally the The states and Canada where the estimates suggest that only 0.3–3.0 and four.0% of dogs are insured, respectively (reviewed by O'Neill et al. [15]). In this study, the recorded percentage of insured animals was highest in dogs, one.five times greater than that of cats, and lowest in rabbits. These findings are similar to those based on a second unlike UK population in veterinary practices using a different PMS (Sánchez-Vizcaíno F: Population demographics, unpublished). Other studies still have shown insurance to be quite variable in dogs (xix.0–40.iii%) [i, 15, 36, 38]. This variation may exist driven by differences in study population, methodology and timing. Of the dogs and cats presented to SAVSNET practices, with the exception of cats from Scotland, the odds of beingness insured were significantly college if their owners were living in the least deprived areas than the most deprived areas, and consistent with our previous pilot study for England and Wales [46]. Information technology seems probable that the insured population of animals is therefore quite different from the uninsured population, with likely impacts on the health of private animals, equally well as the veterinary health seeking behaviour and preventive health care taken by the owner. Studies of wellness brunt based on insured animals may therefore non be generalisable to uninsured animals [12].

Pet microchipping status for each species

Microchipping is one of the all-time means to reunite lost or stolen pets with their owners and reduce the number of pets in shelters. In our population, we institute that the recorded relative frequency of microchipping was higher in dogs than in cats and rabbits, and higher than that reported for dogs in an England-based study past O'Neill et al. [16]. This variation could be driven by differences in the sampled population. As shown by our previous airplane pilot study for England and Wales [46], we confirm here that socioeconomic factors seem to be associated with this intervention. For the dogs and cats attending SAVSNET practices, the odds of being microchipped were significantly college if their owners were living in the least deprived areas of Cracking U.k. rather than the virtually deprived areas. Clearly the contempo introduction of compulsory microchipping of dogs beyond the UK will radically change these proportions in the coming months and years. Withal, this legislation only covers the dog; it will exist interesting to monitor the bear upon on other species as more dogs go microchipped. Compulsory microchipping also provides new resources to explore population demographics, where these tin can ethically exist made available for research [ane].

Information limitations

All results are necessarily based on data as recorded in individual EHRs such that our observations may exist impacted by the quality of data recording in private animals and practices. EHRs are only available from those animals whose owners did not exclude their information by opting out. This report is cross-exclusive in nature so the status of time variable exposures in the study population such every bit the veterinary practice the animal attends, the region the owner lives or the IMD relative to the location of the pet possessor are ascertained but for the fourth dimension in which the study is conducted. In these instances, the investigator cannot exist certain that the exposure preceded the effect (ane of the fundamental criteria for establishing causation). Therefore, this kind of study can produce measures of association simply cannot 'prove' causation.

Veterinary practices contributing data to this study were selected by convenience based on their use of a compatible version of PMS and recruited based on the willingness to take role in SAVSNET. Hence, prevalence of demographic parameters may be very different in this study population compared to those in the overall veterinary-visiting population of small animals across Nifty Britain (target population). Nonetheless, any observed clan between the exposure(southward) and outcome(s) of involvement is more likely to be generalisable, especially, to the source population [47] (i.e. the overall veterinarian-visiting population of modest animals attending veterinarian practices using a SAVSNET compatible version of PMS across Neat United kingdom). This is reinforced by the fact that the practices included in the current study were widely distributed around England, Wales and Scotland and represented 24.five% of those practices that contained the source population and approximately five.six% of those practices that contained the target population in 2009 [1]. It is as well of note that the domestic dog population of this study represented an estimated ii.1% of the Britain dog veterinary-visiting population (information technology would exist higher for Swell Britain) given the assumptions that the dog ownership was 11,599,824 [30] and that 77% of the owned dogs in the state were registered with veterinarian surgeons [1]. Thus, despite the pick bias, the authors have identified and measured the force of potential associations, highlighting areas of interest for futurity research.

It is likewise of annotation that the anonymous nature of both individual animal identification and individual owner identification ways information technology is not possible for the states to tell if the same animal is seen in different practices, nor whether more than 1 creature is owned by the same possessor. And so the potential effect of "possessor" in an outcome of interest could non exist assessed in our models. 1 limitation of using IMD is that it reflects the socioeconomic status relative to the pet owners' location and not necessarily the current socioeconomic status of private owners. IMD is a wider concept than poverty, and is calculated weighting different types of deprivations, or domains that might occur in each Lower layer Super Output Area of England and Wales and each datazone of Scotland. The ranks of some of the domains used in these three countries such equally protection from offense, access to services and living environment are expected to be mostly given past the characteristics of the areas for which they are calculated regardless of the wealth of the individuals living in those areas. Thus, the authors believe that IMD could all the same exist a valuable proxy for a general socioeconomic condition of individual pet owners as people living in the same area necessarily share several types of impecuniousness.

The engagement of birth was not captured in 1.iii% of dogs, cats and rabbits, and 5.four% of owners' postcode, i.3% of fauna species and the breeds of 12.3% of animals were not mapped. This lack of information was considered small-scale when compared with the report population and therefore one would wait that if it were recorded would not modify the overall conclusions obtained from this written report. Conclusions from the age profile at fourth dimension of neutering should be interpreted with caution because in almost half of neutered dogs and 57.7% of neutered cats this information was not recorded in the clinical tape. Information technology is also likely that the age of neutering was non ever authentic as a pocket-size number of animals were recorded to exist neutered just after they were built-in or at a very early age. All the same, these errors were considered negligible when they are seen in the context of the total study population (Fig. 5). Information technology is likewise of note that species and breed classification of animals were as accurate as the practitioner's criterion for its classification was. Univariable mixed effects logistic regression models were used to model the relationships between socioeconomic status and diverse KPIs such as neutering, insurance and microchipping. These associations were only assessed in the context of the veterinary-visiting population of modest companion animals. Futurity analyses, including more explanatory variables like breed, age and sex would broaden the current results, providing farther understanding into owner and veterinary surgeon behaviour.

Conclusions

Up-to-date demographic information are essential for agreement populations at risk, and for exploring the variations inside populations and how these central patterns chronicle to health. This report could only have been accomplished through the seamless collection and use of EHRs at scale from individual veterinary practices. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first time that, past linking individual animals through postcodes to area-based estimates of cloth deprivation, socioeconomic factors accept been investigated with regard to species ownership, brood ownership, microchipping status, and preventive health care interventions such every bit neutering and insurance in both dogs and cats throughout Dandy Uk. In the future, through ongoing drove and longitudinal analysis of these kinds of information, practitioners will be able to monitor and adjust local policies to their prevailing demographics.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EHRs:

-

Electronic wellness records

- IMD:

-

Alphabetize of multiple impecuniousness

- NUTS:

-

Nomenclature of units for territorial statistics

- PMS:

-

Practice management organization

- SAVSNET:

-

The small creature veterinary surveillance network

References

-

Asher L, Buckland EL, Phylactopoulos CI, Whiting MC, Abeyesinghe SM, Wathes CM. Estimation of the number and demographics of companion dogs in the U.k.. BMC Vet Res. 2011;7:74.

-

Downes Thou, Canty MJ, More SJ. Census of the pet canis familiaris and true cat population on the island of Ireland and homo factors influencing pet ownership. Prev Vet Med. 2009;92:140–9.

-

Murray JK, Browne WJ, Roberts MA, Whitmarsh A, Gruffydd-Jones TJ. Number and ownership profiles of cats and dogs in the Britain. Vet Rec. 2010;166:163–8.

-

Robinson NJ, Brennan ML, Cobb M, Dean RS. Capturing the complication of beginning opinion minor animal consultations using direct observation. Vet Rec. 2015;176:48.

-

Stavisky J, Brennan ML, Downes M, Dean R. Demographics and economic burden of un-owned cats and dogs in the UK: results of a 2010 census. BMC Vet Res. 2012;viii:163.

-

Pearson H. Children of the 90s: coming of age. Nature. 2012;484:155–eight.

-

Wright J, Small North, Raynor P, Tuffnell D, Bhopal R, Cameron N, et al. Accomplice contour: the built-in in Bradford multi-ethnic family unit cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:978–91.

-

Pugh CA, BMd B, Handel IG, Summers KM, Clements DN. What can cohort studies in the dog tell us? Canine Genet Epidemiol. 2014;1:v.

-

Welsh CP, Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Murray JK. The neuter status of cats at four and half-dozen months of historic period is strongly associated with the owners' intended age of neutering. Vet Rec. 2013;172:578.

-

Egenvall A, Bonnett BN, Olson P, Hedhammar A. Gender, age and breed blueprint of diagnoses for veterinarian intendance in insured dogs in Sweden during 1996. Vet Rec. 2000;146:551–vii.

-

Egenvall A, Bonnett BN, Olson P, Hedhammar A. Gender, historic period, brood and distribution of morbidity and mortality in insured dogs in Sweden during 1995 and 1996. Vet Rec. 2000;146:519–25.

-

Egenvall A, Nodtvedt A, Penell J, Gunnarsson L, Bonnett BN. Insurance information for inquiry in companion animals: benefits and limitations. Acta Vet Scand. 2009;51:42.

-

Betimes. The Microchipping of Dogs (England) Regulations 2015. In: Parliament, H. o., (ed.). 2015.

-

Lund EM, Armstrong PJ, Kirk CA, Kolar LM, Klausner JS. Health condition and population characteristics of dogs and cats examined at individual veterinary practices in the U.s.a.. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;214:1336–41.

-

O'Neill DG, Church DB, McGreevy PD, Thomson PC, Brodbelt DC. Approaches to canine health surveillance. Canine Genet Epidemiol. 2014;1:2.

-

O'Neill DG, Church building DB, McGreevy PD, Thomson PC, Brodbelt DC. Prevalence of disorders recorded in dogs attending principal-care veterinary practices in England. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90501.

-

Jones PH, Dawson S, Gaskell RM, Coyne KP, Tierney A, Setzkorn C, et al. Surveillance of diarrhoea in small animal exercise through the minor fauna veterinary surveillance network (SAVSNET). Vet J. 2014;201:412–8.

-

Radford AD, Noble PJ, Coyne KP, Gaskell RM, Jones PH, Bryan JG, et al. Antibacterial prescribing patterns in small animal veterinary practice identified via SAVSNET: the pocket-sized animate being veterinary surveillance network. Vet Rec. 2011;169:310.

-

Office for National Statistics. Postcode Products. In: Open Geography, Download products. 2014. http://geoportal.statistics.gov.uk/datasets?q=ONS%20Postcode%20Directory%twenty(ONSPD)&sort=name. Accessed 28 Oct 2014.

-

Department for Communities and Local Government. English indices of deprivation 2010: indices and domains. In: Statistics, English indices of impecuniousness 2010. 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2010. Accessed 17 Oct 2014.

-

The Scottish Government. Function 2 – SIMD 2012 Information – Overall ranks and domain ranks. In: Statistics, Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation, SIMD 2012 Publication Web Portal, Download SIMD 2012 Data. 2012. http://simd.scotland.gov.uk/publication-2012/download-simd-2012-data/. Accessed 17 Oct 2014.

-

Welsh Government. WIMD 2011 individual domain scores and overall alphabetize scores for each Lower Layer Super Output Area (LSOA). In: Statistics & Research, Welsh Index of Multiple Impecuniousness (WIMD), Past releases, 2011. 2011. http://gov.wales/statistics-and-research/welsh-index-multiple-deprivation/?lang=en#?tab=previous&lang=en&_suid=1434998682468013747584768796872. Accessed 17 Oct 2014.

-

Department for Communities and Local Government. English language indices of deprivation 2010. In: Statistics, English indices of deprivation 2010. 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english language-indices-of-deprivation-2010. Accessed 17 Oct 2014.

-

The Scottish Government. Overview of the SIMD. In: Statistics, Scottish Index of Multiple Impecuniousness, SIMD 2012 Publication Web Portal, Introduction to SIMD 2012. 2012. http://simd.scotland.gov.u.k./publication-2012/introduction-to-simd-2012/overview-of-the-simd/what-is-the-simd/. Accessed 17 Oct 2014.

-

Welsh Government. Welsh Index of Multiple Impecuniousness, 2011: Summary report. In: Statistics & Enquiry, Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD), Past releases, 2011. 2011. http://gov.wales/statistics-and-enquiry/welsh-index-multiple-deprivation/?lang=en#?tab=previous&lang=en&_suid=1434998682468013747584768796872. Accessed 17 Oct 2014.

-

Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. 2nd ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2002.

-

R Core Squad. R: language and environment for statistical computing. In: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2015. http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 22 June 2015.

-

Lopez AD, Begg Southward, Bos E. Demographic and epidemiological characteristics of major regions, 1990–2001. In: Lopez Advertizing, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL, editors. Global burden of illness and risk factors. New York: Oxford University Printing; 2006. p. 17–44.

-

Robinson NJ, Dean RS, Cobb M, Brennan ML. Investigating common clinical presentations in get-go opinion pocket-size animal consultations using direct observation. Vet Rec. 2015;176:463.

-

Murray JK, Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Roberts MA, Browne WJ. Assessing changes in the UK pet true cat and dog populations: numbers and household ownership. Vet Rec. 2015;177:259.

-

Leaderer BP, Belanger K, Triche Due east, Holford T, Gold DR, Kim Y, et al. Dust mite, cockroach, true cat, and canis familiaris allergen concentrations in homes of asthmatic children in the northeastern United states: bear upon of socioeconomic factors and population density. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:419–25.

-

Kitch BT, Chew G, Burge HA, Muilenberg ML, Weiss ST, Platts-Mills TA, et al. Socioeconomic predictors of high allergen levels in homes in the greater Boston area. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:301–7.

-

Murray JK, Gruffydd-Jones TJ. Proportion of pet cats registered with a veterinary practice and factors influencing registration in the UK. Vet J. 2012;192:461–6.

-

Kennel Lodge. Tiptop 20 Breeds 2013–2014. In: Brood registration statistics. 2015. http://www.thekennelclub.org.united kingdom/media/350279/2013_-2014_top_20.pdf. Accessed 4 June 2015.

-

British Veterinary Clan. Neutering of cats and dogs. In: News, campaigns and policy. Policy. Companion animals. 2015. http://www.bva.co.u.k./News-campaigns-and-policy/Policy/Companion-animals/Neutering/. Accessed 5 June 2015.

-

O'Neill DG, Church building DB, McGreevy PD, Thomson PC, Brodbelt DC. Longevity and bloodshed of owned dogs in England. Vet J. 2013;198:638–43.

-

Diesel G, Brodbelt D, Laurence C. Survey of veterinary practice policies and opinions on neutering dogs. Vet Rec. 2010;166:455–8.

-

VetCompass. Demographic data on UK pets. 2015. http://www.rvc.ac.uk/vetcompass/infographics/united kingdom. Accessed 20 May 2015.

-

Looney AL, Bohling MW, Bushby PA, Howe LM, Griffin B, Levy JK, et al. The Association of Shelter Veterinarians veterinary medical care guidelines for spay-neuter programs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;233:74–86.

-

The Cat Group. Policy argument one: Timing of neutering. In: policy statements. 2006. http://world wide web.thecatgroup.org.uk/policy_statements/neut.html. Accessed twenty May 2015.

-

The Cat Group. Cat neutering practices in the Britain. J Feline Med Surg. 2011;13:56–62.

-

Howe LM. Short-term results and complications of prepubertal gonadectomy in cats and dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1997;211:57–62.

-

Aronsohn MG, Faggella AM. Surgical techniques for neutering 6- to 14-week-erstwhile kittens. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993;202:53–5.

-

Olson PN, Kustritz MV, Johnston SD. Early on-age neutering of dogs and cats in the Usa (a review). J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2001;57:223–32.

-

Spain CV, Scarlett JM, Houpt KA. Long-term risks and benefits of early-age gonadectomy in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;224:372–ix.

-

Jones PH, Buchan I, Dawson S, Gaskell RM, Radford Advertizing, Setzkorn C, et al. The social distribution of veterinary intendance. Society for Veterinarian Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine (SVEPM); 28–thirty March 2012; Glasgow (United kingdom). 2012.

-

Dohoo I, Martin W, Stryhn H. Introduction to observational studies. In: Dohoo I, Martin Due west, Stryhn H, editors. Veterinary epidemiologic enquiry. 2d ed. Charlottetown, Prince Edward Isle, Canada: VER Inc; 2009. p. 151–66.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank data providers both in practice (VetSolutions, Teleos, CVS and non-corporate practitioners) and in diagnostic laboratories, without whose support and participation, this research would non exist possible. We would also like to give thanks Susan Bolan, SAVSNET project administrator, for her help and back up.

Funding

SAVSNET is supported and major funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) (www.bbsrc.ac.britain) and the British Small Beast Veterinary Clan (BSAVA) (www.bsava.com), with boosted sponsorship from the Brute Welfare Foundation (www.bva-awf.org.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland). FSV is fully supported, and ADR partly supported by the National Institute for Wellness Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections (world wide web.hpruezi.nihr.air conditioning.uk) at the University of Liverpool in partnership with Public Health England (PHE), in collaboration with the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. The views expressed are those of the authors and non necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health or PHE. The article processing charge was funded by University of Liverpool. The funders had no role in study design, data drove, assay and estimation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to problems of companion brute owner confidentiality, but are bachelor on asking from the SAVSNET Data Access and Publication Panel (savsnet@liverpool.ac.uk) for researchers who see the criteria for access to confidential data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The report was conceived and designed past: ADR, FSV, P-JMN, PHJ, IB, SD and RMG. The funding for the project was acquired by: ADR, P-JMN, PHJ, SD, SE and RMG. The database was developed by: TM. The information were acquired past: ADR, FSV and SR. The information curation was carried out past: FSV. The methodology, formal analysis and visualisation was conducted by: FSV. The manuscript was drafted by: FSV and ADR. The manuscript was revised critically for of import intellectual content past all authors who take too read and approved the last manuscript. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Respective writer

Ideals declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this project came from the Academy of Liverpool Commission on Research Ideals (CORE) (RETH00964). Consent to participate is recognised via an opt-out process available to all companion animal owners at veterinary clinics participating in SAVSNET. Specifically, owners attention clinics participating in SAVSNET are informed virtually the project past a waiting room affiche; those wishing to opt out are invited to tell their practitioner, who can then exclude all their information from the study. These opted out consultations are quantifiable for each exercise, but no further data are captured past SAVSNET. There is no explicit requirement to bank check each owner has seen the poster because this would not be practical in a busy practice. This consenting process was felt proportionate to the risk by the ethics commission as we only collect anonymised information, and merely data relating to the consultation in question (we do not collect the full wellness record).

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher's Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Boosted files

Additional file i:

Demographics of the SAVSNET veterinarian-visiting population of dogs, cats and rabbits past each region considered in the study. (DOCX 18 kb)

Additional file 2:

Demographics of the SAVSNET veterinarian-visiting population of dogs and cats summarised at practice level. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file iii:

Number of animals stratified by species, British land and Alphabetize of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). Species assessed include dogs, cats and other species. IMD category 1 indicates the least deprived areas and category 5 the most deprived. The pct that each species made upwardly within each IMD category in each country is shown in brackets. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 4:

Results of the mixed effects logistic regression models, assessing the association between a range of an animal's characteristics and the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). Shown are odds ratios of stock-still effects IMD in England, Wales and Scotland from the last mixed furnishings logistic regression models of; the probability of animals being a dog in the veterinarian-visiting population; the probability of animals being a cat in the veterinary-visiting population; and of the probability of dogs and cats being purebred in the veterinary-visiting dog and cat population, respectively. 3 asterisks (***), 2 asterisks (**) and i asterisk (*) indicate p < 0.001, p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively. CI = confidence interval. (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 5:

Results of the mixed effects logistic regression models, assessing the association betwixt a range of an animate being's key operation indicators and the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). Shown are odds ratios of fixed effects IMD in England, Wales and Scotland from the terminal mixed effects logistic regression models of; the probability of dogs and cats beingness neutered by sex; the probability of dogs and cats beingness insured; and of the probability of dogs and cats being microchipped. Asterisk (*) indicates p < 0.05. CI = confidence interval. (DOCX xix kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you requite appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Eatables license, and betoken if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez-Vizcaíno, F., Noble, PJ.Yard., Jones, P.H. et al. Demographics of dogs, cats, and rabbits attending veterinary practices in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland every bit recorded in their electronic health records. BMC Vet Res 13, 218 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1138-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12917-017-1138-ix

Keywords

- Demographics

- Companion animals

- Electronic health records

- Socioeconomic factors

- SAVSNET

Source: https://bmcvetres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12917-017-1138-9

Posted by: archiemuchey.blogspot.com

0 Response to "2. What Is A Type Of Veterinarian That Only Practices On Small Companion Animals?"

Post a Comment